Foreign businesses paid $40B in taxes to the Kremlin for two years since the invasion of Ukraine. To encourage companies to exit Russia, the G7 governments have a responsibility to define expectations for businesses that are currently not subject to sanctions.

The amount of taxes paid by all foreign companies operating in Russia in 2022-2023 may amount to $20 billion (€18.6 billion) annually, according to a new report from the B4Ukraine Coalition.

Based on data from the Kyiv School of Economics (KSE), the analysis found that as of February 2024, only a small number — 358 foreign firms — have completed a full exit from Russia through sale or liquidation. 2,138 foreign businesses with Russian subsidiaries at the start of the invasion remain in the aggressor country, indirectly contributing to the war through corporate taxes, supply chains and assistance to the Kremlin with its mobilization efforts, as per requirements of the Russian Partial Mobilization Order.

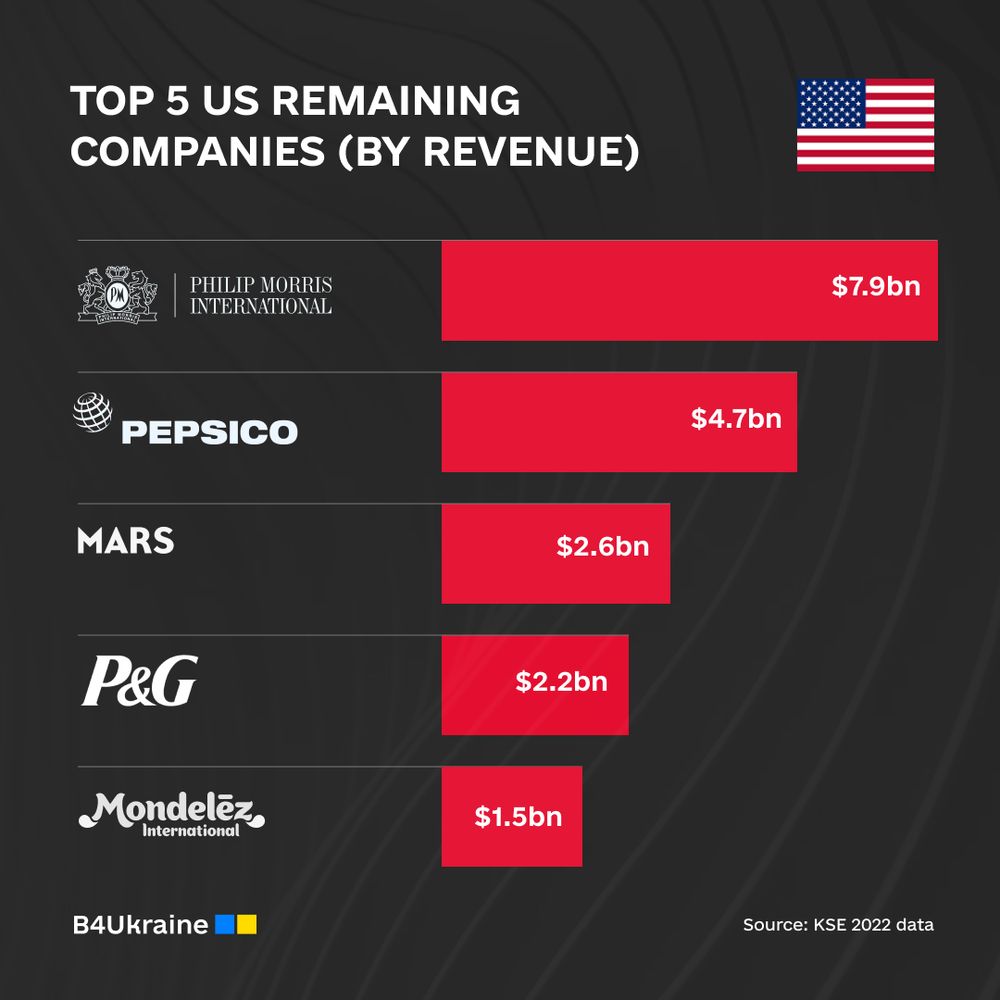

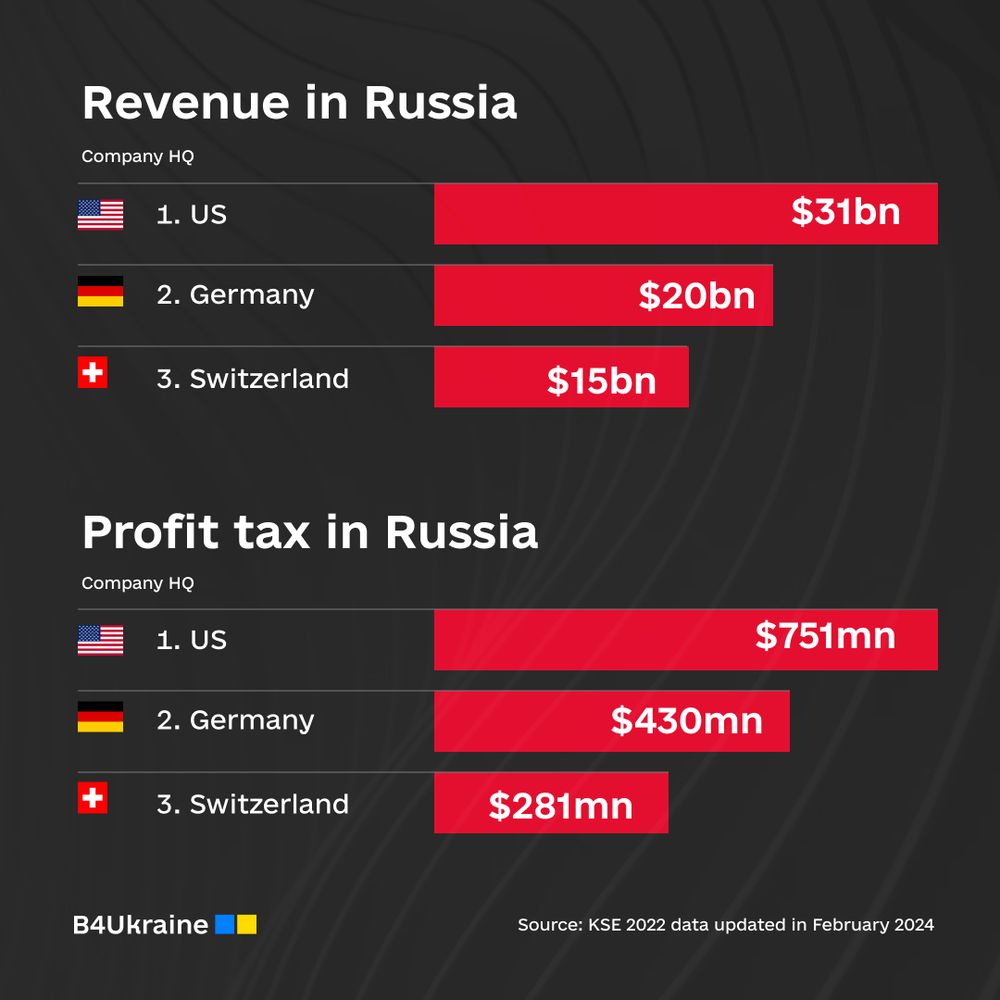

American, German and Swiss companies are the most profitable in Russia and have paid the highest amount of profit tax to the Kremlin in 2022, according to a B4Ukraine analysis of the KSE data. There are currently 330 American and 277 German firms in Russia — including Mondelez International, Philip Morris, PepsiCo, Mars, Metro AG, Bayer and Siemens Energy AG.

This reality is counterproductive as coalition countries, with the US and Germany being the largest bilateral donors to Ukraine, have collectively contributed $100 billion in humanitarian, financial and military aid since the invasion. The presence of these companies in Russia undercuts the substantial military and economic assistance as well as diplomatic and moral support that their home country governments have extended to Ukraine as it fights for survival.

Fast-moving consumer goods companies (FMCGs) such as Mondelez International, Unilever, PepsiCo, Procter & Gamble, Nestlé, and Mars are amongst the highest earners in Russia, having generated $17.6 billion (€16.3 billion) of revenue in 2022. What sets them apart is the use of similar justifications to remain in the market of the aggressor state. They argue to provide ‘essential’ goods and show deep concern for the welfare of their Russia-based employees.

While the essentiality argument is applicable in a handful of cases involving a selective group of companies and industries (such as pharma companies providing life-saving medicines), the FMCG sector players have been deliberately stretching the definition of essentiality to include chocolates, biscuits, and aftershave.

The employee welfare argument is also difficult to reconcile with the obligation companies face in regards to Russia’s Partial Mobilization Order as they must help with recruitment of eligible employees and the provision of material support deemed necessary by the Russian state.

According to KSE, the average share of revenue generated in Russia relative to the global share is only 3%. Research also shows that most of those public companies that exited first were able to compensate for the lost share of the Russian market with increased prices of their shares and higher market capitalization.

The refusal to leave Russia also legitimizes the war in the eyes of Russian consumers who are still able to buy the products of many Western brands while their Armed Forces are committing war crimes and crimes against humanity. But most importantly, such a substantial business presence of Western companies highlights an acute need for government intervention in the form of business advisories (guidance) to their businesses remaining in the aggressor state.

The time is now for the G7 governments to step up their efforts and fully isolate the Russian economy. In the case of non-sanctioned companies, the G7 governments should issue guidance to their business, which set out an expectation to responsibly exit Russia to avoid complicity in war crimes. 2024 is the year to defund Russia’s war and to ensure that Ukraine can restore its sovereignty and territorial integrity.